How ceramics are made

The process

To shape the clay into the desired form, humans have used various techniques.

Coil construction. This involves preparing sticks or strips of clay that are placed fresh, one on top of the other, to form a container. The strips are then well blended together with fingers, and the exterior is carefully smoothed.

Mold construction. This involves preparing a model (mold) with an inverse and opposite shape to the object to be obtained. The clay, in a very fresh state, is pressed onto the mold to fill all the empty spaces. The two parts can then be easily separated after drying due to the significant volume reduction of the clay, caused by the evaporation of the water it contains.

Wheel throwing. By the end of the 4th millennium BC, humans invented the potter’s wheel, which saves a lot of time in making clay pots. The wheel not only offers significant precision but also allows for the mass production of objects of the same size on a circular base.

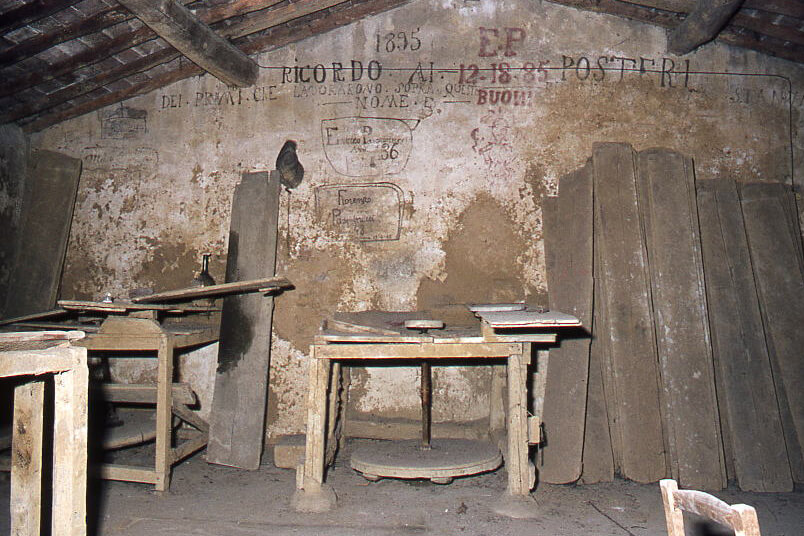

The ancient wheel

Before the discovery of electricity, ancient kilns used human power to move the wheels.

Already in the Middle Ages, the potter’s wheel took on the appearance it maintained until a few years ago; this wheel is still widely used in countries where modern technology is less prevalent.

The ancient wheel is a very simple machine, consisting of two wheels of different sizes, one much larger and heavier than the other, connected by a shaft.

The larger wheel is placed at the bottom so that pushing it with the foot causes an identical rotation in the smaller one.

The inertia of the lower wheel, due to its greater weight, allows the potter not to continuously push the machine and especially to work the clay without the rotation stopping abruptly.

This simple mechanism was integrated into a bench where the operator, called a turner, could sit.

The coatings

The coatings used in medieval and post-medieval (Renaissance, modern) European ceramics were essentially of three types:

1) Ceramics with a transparent or semi-transparent coating, also known as glazed ceramics, achieved with simple lead oxide or with added colorants.

4) Ceramics with an opaque earth-based coating, known as engobed ceramics, protected by a layer of glossy glaze.

5) Ceramics with a coating, known as majolica, based on silica, tin oxide, and lead, with a glossy white background.

Once the clay or pottery works have been shaped, they must be fired after being gradually dried.

Unless the quality is good enough to allow reaching very high temperatures, clay firing results in a porous product (the biscuit), which absorbs liquids but can be made waterproof by applying one of these types of coatings.

The substances used to achieve said coating (glaze, enamel) are usually absorbed by the ceramic through immersion.

In the case of engobes, it involves using particularly purified types of clay that are found in nature, while it is essential to manufacture a compound called marzacotto in order to achieve any silica and metal oxide-based coating.

Color preparation

To color ceramics already equipped with a metallic coating, colors made from metal oxides were also used.

In essence, the process remains the same to this day.

Colors can be divided into two categories: simple ones formed by the oxide of a single metal and compounds obtained by mixing different metals and other substances.

The ceramic painter cannot always see the final color that the substance will take on before the second firing.

Colors, in fact, achieve their brilliance only after being fused again in the kiln.

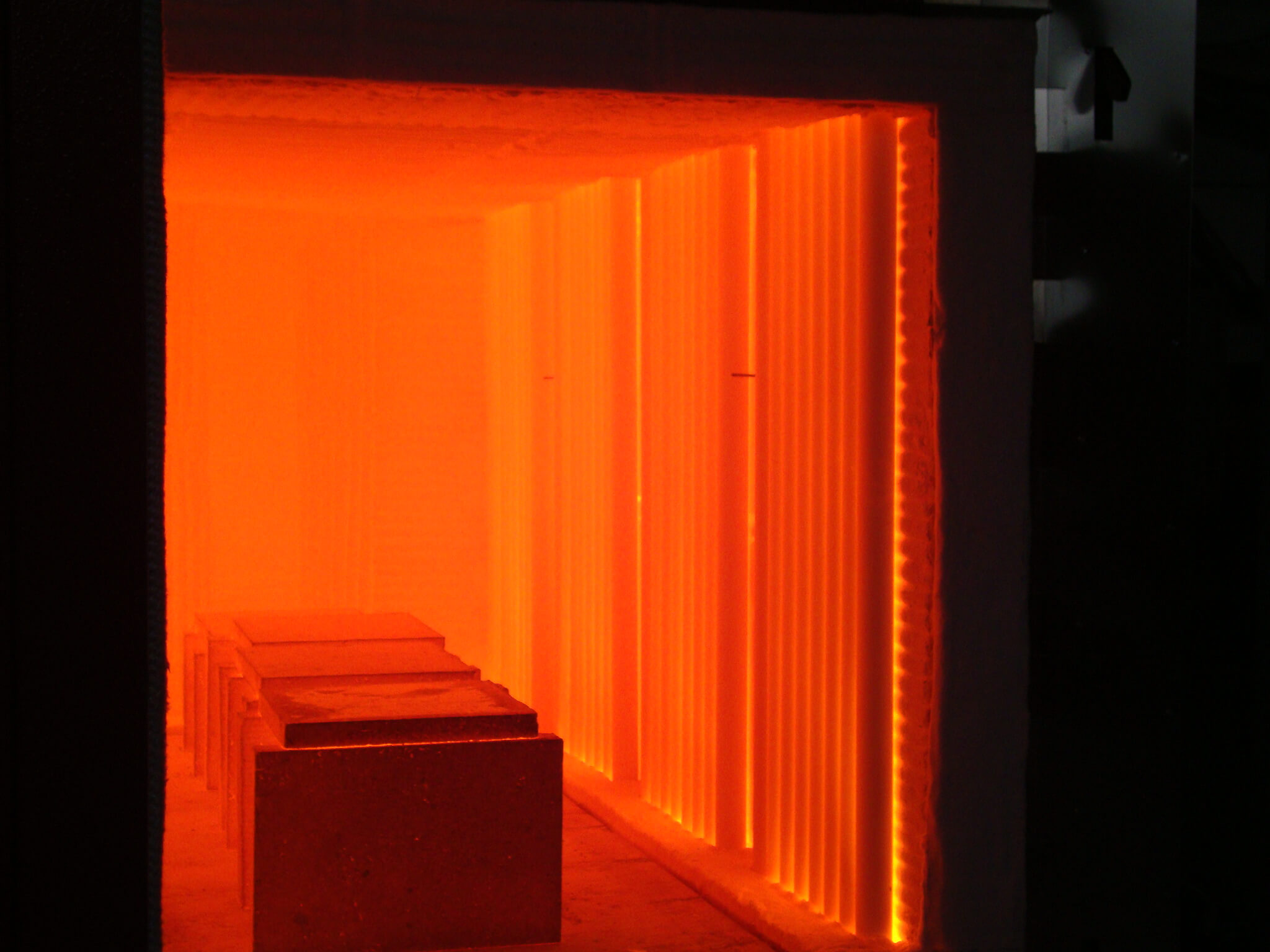

The reverberatory furnace

In order to complete all the operational phases required to prepare silica-metallic coatings (glazes and enamels) and colors, metals were calcined (artificial oxidation) using a special oven, called a furnace or small kiln.

It was a two-chamber oven, separated by a dividing wall that did not reach the vault.

In the smaller side of the kiln, a fire was lit through a small opening.

The other chamber of the oven would vent the flames all the way through the chimney, without contaminating it with combustion residues.

For this peculiarity, it was also called a reverberatory furnace (i.e., with indirect flame).

During the phase of metal fusion in the kiln, an operator, maneuvering a heavy hoe-shaped tool (zappone), fixed with a chain at its center of gravity, agitated the surface of the molten metal, facilitating the combinations (agreement) between different metals and their oxidations.

In the reverberatory furnace, all the metal oxides necessary for ceramic processing were manufactured, and marzocco was added to them; these compounds were then finely ground using hydraulic mills, moved wither manually (grinders) or by animals.

Glazing-Enameling-Decoration

To fix a metal oxide-based coating film on a piece of ceramic fired once, the biscuit was, in the past as today, immersed in a tub containing the glaze or enamel, in the form of a finely ground compound extended with water.

The immersion (dipping) is carried out by operators called dippers, who must take care not to touch the piece to be immersed with their hands, as the natural oiliness of the skin would prevent the metallic substances from adhering well to the biscuit.

The biscuit, due to its porosity, quickly absorbs the more liquid part of the compound, leaving the metallic parts on the surface.

In the case of majolica, once dry, the ceramic dipped in enamel can be decorated by painting or scratching the colored parts superficially.

FIRING AND DECORATION

The techniques of the final stages of ceramic processing

The kiln

The simpler ceramic kiln consisted of a lower part (also called an ash pit), intended to house the fuel, and an upper firing chamber, through which the fire, emerging from the ash pit, had to pass, filtered by numerous holes that were opened in the floor.

The more advanced kiln features the addition of a third chamber, also called a small kiln, placed above the main firing chamber.

Since it was near the chimney dedicated to flame exhaustion, combustion residues (smoke and soot) accumulated here: therefore, this was the firing chamber intended to produce the biscuit, which could not be damaged by such residues, as it lacked melting coatings.

Another type of kiln was the muffle kiln, in which the flames passed through an external gap without touching the objects meant to be fired.

The muffle kiln could also become a reducing atmosphere kiln when oxygen was removed from the firing chamber.

This operation was usually carried out by introducing substances that, when heated, produced abundant smoke.

After being fired for a third time (third firing) at a moderate temperature (about 650°C), the colors used in decoration would become iridescent and take on metallic reflections.

Stacking

The firing phase of the artifacts was a particularly delicate operation, to which particularly experienced people called kiln workers were dedicated. To make the most of the fuel, they tried to fill the kiln with as many objects as possible, arranging them one on top of the other in orderly stacks (stacking).

Artifacts with silica-metallic coatings (glazed or vitrified) were spaced with special supports, which very often took the form of a tripod, as they still do today, to prevent the fusion of the coating from welding them together during firing.

In traditional kilns (not in muffle types) to prevent flames and other combustion residues (smoke, soot, dust) from damaging the glazes or vitrines, the artifacts to be fired were placed in special containers, called boxes or cases, within which they were spaced using small triangular supports inserted into the walls and protruding towards the inside of the cases themselves.

Once filled, the kiln was sealed by closing the access door (usciale) to the firing chamber with a temporary wall: the fire was thus forced to vent outward by passing through it completely.

Firing

The first phase of the kiln lighting involved the use of small-sized wood (stipa) that burned easily and evenly, quickly bringing the firing chamber to the desired temperature.

In order to preserve the color of the ceramics, they would often keep feeding the fire with large wood.

Ceramic firing lasted at least 11-12 hours, during which the kiln worker made sure to keep the optimal temperature (about 900, by adding or removing wood with special forks or prongs, to maintain the optimal temperature for firing the pots (for majolica about 900°C).

In the absence of temperature control instruments, the kiln worker relied on their experience, determining the approximate degree of temperature from the color that the inside of the kiln took on, which is always greater in the different gradations that lead from red to white.

At regular intervals, the kiln worker extracted with a special iron tool (lookout) a small pot (test, procella) placed in the kiln in a position accessible from the outside, to verify the progressive degree of firing of the objects.

When it was believed that the pieces were sufficiently fired, the kiln was turned off and allowed to cool gradually, for at least a day.

Subsequently, the temporary closure of the usciale was demolished, and the finished product was extracted.

Decoration

We can distinguish three fundamental methods used in the past in ceramic decoration: they are painting, sgraffito, and the addition of clay substances in relief.

While painting involves applying one or more colors with a brush over the surface, the sgraffito method is based on removing the coating (engobe or enamel) when it is still in a fresh state, using a pointed tool or a prong (stick).

In engobed and sgraffito ceramics, the superficial engobe layer is removed to reveal the reddish color of the underlying biscuit: with this system (sgraffito with a point), the outlines of the figures are drawn, which can then be perfected by painting them.

It is called sgraffito with a lowered background when the outlines are engraved by removing more extensive parts of engobe with a wide-pointed tool or prong.

The method of adding material in relief, usually of the same clay nature as the biscuit, was widely used in Northern Europe (Northern Germany and England) in ceramics known as slipware.

For painted decoration, particular artifices have also been prepared that make the color take on a raised position on the surface of the decorated object.

In Spain, the lines dividing the decorations were defined with a cord impregnated with fatty substances that, preventing the colored glazes from adhering during firing, caused them to retract. By burning the cord, areas were left uncovered where the color would not adhere due to the fatty substances; this allowed the decoration to maintain well-defined margins.

This method is called cuerda seca.